Teck Smelter’s massive mercury discharges

Below is a 2004 article written Karen Dorn Steele and published in the Spokesman-Review. It is regarding the massive amount of toxins that Teck dumped into the river for decades.

The discharge amounts are from the smelter’s own records and documentation filed with the B.C. Ministry of Environment. The smelter was forced to hand over the information to the reporter due to the Freedom of Information Act.

Teck representatives are quoted as trying to deny and downplay some of the data. Since 2004, when the article was published, all of the discharge amounts of toxins stated in the article have been confirmed.

Although much has happened since this 2004 article, the information provided in this article regarding the specific toxins and the actual amounts discharged by Teck is the most informative and straight forward article I have found.

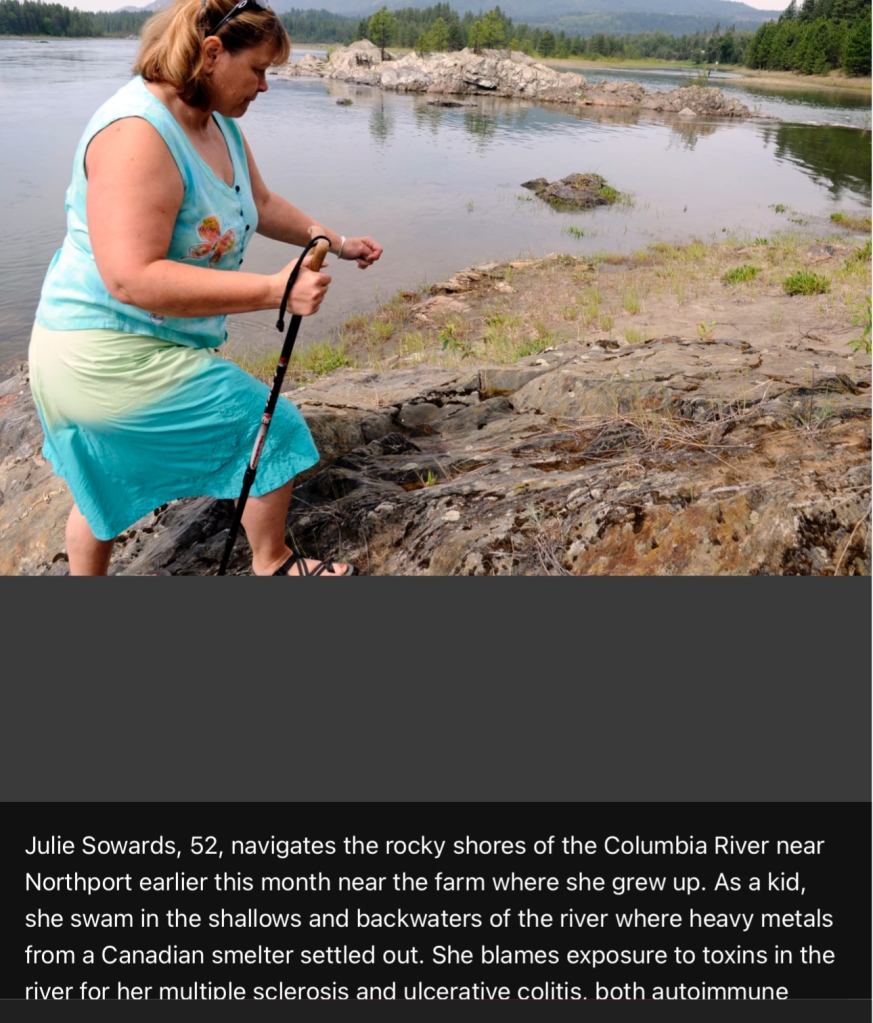

It also speaks volumes to the decades of debate regarding the role Teck’s pollution has played in the clusters of health issues being found in Northport residents and in other communities and tribes along the Upper Columbia River.

It is not a very long article – I beg you to take a moment and read it. The information is unbelievable.

________________________________________________________

B.C. Smelter Dumped Tons of Mercury

Records show scope of river pollution

Karen Dorn Steele

Staff writer

June 20, 2004

A Trail, B.C., smelter at the center of a diplomatic dispute between the United States and Canada over Superfund cleanup has dumped tons of highly toxic mercury into the Columbia River over decades, newly obtained documents reveal.

The smelter’s record of dumping millions of tons of contaminated slag has been known for years. But until now, little has been known about the extent of the smelter’s mercury pollution.

An October 1981 memo from British Columbia’s Ministry of the Environment describes extensive mercury releases from the Teck Cominco Ltd. smelter six miles north of the border with Washington. The memo and dozens of other documents on the big lead and zinc smelter were obtained by The Spokesman-Review under British Columbia’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

“Large amounts” of mercury – approximately 20 pounds a day – “have been deposited in the Columbia over many years by Cominco,” the 1981 Canadian memo says. It notes that mercury in the river is a problem “due to the long time effects and strong potential for interboundary pollution.”

Mark Edwards, Teck Cominco’s manager for environment, safety and health, doubts the plant’s releases in the early 1980s were that high. The company estimates the smelter released 9 pounds of mercury into the Columbia each day – and has since reduced releases to .07 pounds a day, Edwards said.

Calculations based on the two Canadian estimates show that between 1.6 tons and 3.6 tons of mercury were discharged to the river each year since the 1940s, when the smelter expanded for wartime production. It was built in 1896 but was much smaller at the turn of the century.

Washington state officials were surprised by the mercury numbers obtained by the newspaper. They have had only sporadic reports on mercury and other pollutants discharged to the Columbia

in Canada, said Flora Goldstein, director of the Washington Department of Ecology’s toxics program in Spokane.

“We weren’t aware of the quantities you are talking about. The province and the company have not been forthcoming about this,” Goldstein said. In 1995, Ecology officials and their Canadian counterparts agreed to share more information on river spills.

Mercury is a highly toxic metal that can be inhaled, ingested or absorbed through the skin. It builds up in the tissues of fish. In sufficient doses, it can cause neurological damage to the developing brain of the human fetus, and it builds up in the breast milk of nursing mothers.

The Colville Confederated Tribes, which petitioned the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1999 to study the pollution, has produced a new report that says the Trail smelter out-polluted all U.S. companies reporting discharges to American rivers and streams in the mid-1990s.

While only the “tip of the iceberg,” the scope of the smelter’s water pollution from 1994 to 1997 is amazing, said Valerie Lee, president and founder of Environment International Ltd., Seattle consultants to the Colvilles. Lee, an engineer and a Yale-educated lawyer, formerly prosecuted environmental cases at the U.S. Department of Justice.

“The Canadian government knew the Trail smelter was causing problems in the United States – and they did nothing. At the smelter, you have very lax standards, very frequent violations and no enforcement. In the United States, if we’d seen a pattern and practice like this, it would have been a criminal case,” Lee said.

Teck Cominco’s Edwards said he hadn’t seen the Colville report and questioned the analysis.

“It’s not necessarily a fair comparison. I doubt they are comparing apples with apples,” Edwards said. “I don’t have the impression that our practices were out of keeping with those of the day.”

Top Polluter

Teck Cominco officials are resisting a Dec. 11, 2003, EPA order to study the contamination, saying U.S. cleanup laws don’t apply to them. They’ve offered an alternative study that would sidestep Superfund cleanup regulations. U.S. and Canadian diplomats are discussing the standoff behind closed doors.

The Trail smelter dumped up to 13.4 million tons of heavy metals-tainted slag into the Columbia from 1896 to 1996, when Canadian regulators ordered a halt to the practice. The slag was carried downstream by the fast and free-flowing Columbia into Lake Roosevelt, the 130-mile impoundment of the river behind Grand Coulee Dam.

In July 2001, smelter operator Cominco Ltd. was merged with Teck Corp., a leading Canadian mining company, to form Teck Cominco Metals Ltd.

The Colvilles’ report compares the smelter’s total reported discharges of dissolved metals to the Columbia from 1994 to 1997 with discharges reported to the U.S. government’s Toxic Release Inventory from U.S. companies to American surface waters in the same years. The consultants didn’t analyze releases before 1994 and didn’t look at airborne releases.

Teck Cominco “discharged to the Columbia River more arsenic, cadmium and lead than all U.S. companies reporting water discharges,” the report says.

In 1994 and 1995, the discharges exceeded the cumulative totals for all U.S. companies for copper and zinc. Mercury discharges were less than the U.S. total, but they were equivalent to 40 percent, 20 percent and 57 percent of all the U.S. releases to water in 1995, 1996 and 1997, the report notes.

In 1997, Cominco built a new smelter at Trail that has helped reduce discharges by 99 percent. But monitoring reports show the company at times continues to exceed its Canadian permit limits for mercury and other heavy metals.

On 86 days between September 1987 and May 2001, Cominco reported spills, including 1,923 pounds of mercury. Cominco was charged twice over the spills in 1989 under Canada’s Waste Management Act. It pleaded guilty and was fined $30,000 by the Rossland Provincial Court.

Big Spill

The B.C. documents from the early 1980s were obtained by the newspaper after a lengthy Canadian government review.

The documents were written in response to a huge spill of 6,300 pounds of mercury to the Columbia from March 19 to March 22, 1980, that Cominco didn’t report to authorities for five weeks. Some 15 tons of sulfuric acid also was released to the air, producing a “visible plume” on March 19, the Canadian ministry said.

The incident triggered a diplomatic protest from the United States, the documents show. After a protracted legal battle, the company was fined $5,000 – Cominco’s first fine. The province could have fined the company up to $1 million.

“Cominco fought back hard. To that date, they’d never been convicted of any environmental offenses,” said Don Skogstad, a Nelson, B.C., lawyer now in private practice who prosecuted the Cominco case for the province.

Shortly after the spill, mercury levels in Lake Roosevelt exceeded drinking water standards and mercury levels in walleye approached the Canadian safety margin of 0.5 micrograms per gram net weight, according to an October 1981 letter from Environment Canada to the B.C. Ministry of Environment.

Environment Canada urged the province to set stricter mercury discharge levels for the smelter.

That eventually happened, Edwards said.

“The contents and quantities of every (pollutant) have been systematically reduced through the permitting process,” he said.

A summary report on the 1980 accident was written by R.H. Ferguson, director of pollution control for the B.C. Ministry’s waste management branch. On March 19, 1980, plant workers noticed a problem with discharges from the No. 8 sulfuric acid plant’s cooler stack and shut down the plant.

“When the bolts on the access manhole cover were loosened, sulphuric acid began to flow out,” the report says.

It was flushed into a sewer “and eventually to the Columbia River” but wasn’t tested for mercury, the report notes.

On April 18, after the company completed analysis of a routine sample taken from the sewer on March 25, an “abnormally high mercury concentration” was noted. The Columbia downstream of Trail also showed very high mercury concentrations. On April 25, Cominco finally reported the loss of an estimated 6,000 pounds of mercury to regulators.

Late Notice

Ferguson recommended prosecuting Cominco for failing to comply with its 1978 discharge permit. He said the incident was caused by “a general lack of training, awareness and concern by all levels of staff within Cominco Ltd.’s Trail operations.” He said it was “inexcusable” for Cominco to have cleaned out the tank without determining the composition of the material to be released to the river.

“Since the turn of the century, the Columbia River has been used by the company as a repository for a vast array of its highly contaminated wastes, sludges and accidental spills. The attitude of its employees that such discharges are legitimate and will not have adverse long-term environmental impacts on the Columbia River appears widespread,” Ferguson wrote.

Carl Johnson, a B.C. regulator who formerly worked as a Cominco engineer, inspected the plant in April 1980 after the spill. In his report, he said he learned that the workers who cleaned up the sulfuric acid plant encountered “elemental mercury droplets” and had wiped them up with rags. Today, plant managers would require protective equipment and special vacuums to clean up mercury, Edwards said.

In May 1980, the U.S. State Department sent a terse diplomatic note to Canada’s External Affairs Ministry. The United States “is greatly concerned that despite the known potential of mercury for causing injury to health and property, U.S. federal and state officials did not receive notice of this spill until April 25, five weeks after the incident occurred,” the diplomatic note says.

The State Department asked for a full report and a technical analysis of the spill’s impacts.

Canadian officials replied July 5, saying they also hadn’t learned of the spill for five weeks. The same day the Canadian Department of the Environment was informed, it informed the EPA, they said.

Monitoring downstream showed an increase in mercury levels “which were nevertheless well within drinking water standards,” the Canadian note said. It also said “appropriate action” was being taken.

Ferguson provided an update to the Washington Department of Ecology’s John Spencer. He said mercury south of the smelter near the U.S. border “is primarily attributable to historic discharge of slag from the metallurgical operations at Trail, rather than the recent acid cooler sludge spill.”

Little Information

Another B.C. official disagreed. Rick Crozier, a biologist with the environment ministry in Nelson, said the recent mercury increases in the sediments after the 1980 accident were “more than would be expected” from the slag deposits, which contain low levels of heavy metals.

In May 1980, the B.C. ministry tested fish south of the smelter. Rainbow trout tissue showed mercury levels twice Canada’s .5 parts per million safety levels south of the plant. In July, further tests showed that sport fish had mercury levels under that level, but bottom-feeding squawfish had mercury levels of .79 ppm.

A year later, Canadian and U.S. officials met at Grand Coulee Dam to discuss mercury levels in Lake Roosevelt. “There appears to be little concern given to the large amounts of heavy metals which are settling on the reservoir bottom,” a July 1981 Canadian government memo says.

The big mercury spill wasn’t Cominco’s only accident in the early 1980s. From March 1980 to October 1981, the plant also spilled 4,500 gallons of ammonia, 1,471 tons of sulfuric acid, 24 tons of phosphate and 9.5 tons of zinc into the river, according to the B.C. environment ministry. Company documents show that from 1980 to 1996, average discharges for dissolved metals were as high as 40 pounds per day of arsenic, 136 pounds of cadmium, 440 pounds of lead, 16,280 pounds a day of zinc and 9 pounds of mercury.

In October 1981, Environment Canada told the B.C. ministry that Cominco wasn’t meeting its discharge limits and said “further action” was necessary. It cited the Boundary Waters Treaty with the United States, which says transnational waters “shall not be polluted on either side to the injury of the health or property on the other.”

Following a July 1988 internal memo from senior toxicologist John Ward, B.C. officials debated whether to warn the public about elevated mercury levels in fish downstream of the smelter. They decided against a warning, saying people were probably safe if they only ate one meal of fish a week.

The following year, the Washington Department of Social and Health Services said more studies of Lake Roosevelt were needed because fish exceeding mercury levels had been found on the Canadian side of the border at Waneta.

Nobody had looked closely at Lake Roosevelt sediments.

Plan Sidelined

A 1991-1993 report from the Columbia River Integrated Environmental Monitoring Program said water quality criteria for heavy metals, including mercury, were exceeded on the Canadian stretch of the Columbia south of the Cominco smelter. The metals concentrations were “highly variable,” but were as much as 40 times greater downstream of the smelter than at any other location, the report said.

In the early 1990s, a Washington resident expressing concern about mercury in Lake Roosevelt contacted the EPA’s regional office in Seattle. EPA emergency response coordinator Thor Cutler worked up a plan to investigate mercury in Lake Roosevelt sediments, but it wasn’t pursued.

“It was a management call. At the time, it appeared that money was better spent on more immediate emergencies,” Cutler said.

Cutler said he had “no knowledge” of Teck Cominco’s pollution legacy or the amounts of mercury that the Canadian smelter was putting into the river – including the 1980 spill of 6,300 pounds.

After the 9,000-member Colville tribe petitioned EPA to determine whether Lake Roosevelt should be declared a Superfund site, EPA did a preliminary survey. In March 2003, the EPA said it had found widespread industrial pollution in sediments throughout the upper Columbia, including elevated lead levels near Northport, high mercury levels near Kettle Falls and high zinc levels near the border with Canada.

After EPA issued its unilateral order to Teck Cominco in December to start studies under U.S. Superfund standards, Cominco offered to spend up to $13 million but maintains it’s not subject to Superfund.

According to Inside EPA, a trade publication, Canadian officials are proposing a new bilateral panel to develop a cleanup plan under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909. A Freedom of Information Act request for the Canadian proposal was rebuffed by the State Department, which said all documents on the diplomatic talks are “predecisional” and therefore confidential.

The Canadians are awaiting a response from the U.S. government, Edwards said.

Meanwhile, the EPA is using Superfund dollars to move ahead with its own study of Lake Roosevelt and the upper Columbia, said EPA project manager Cami Grandinetti. An examination of mercury levels is part of the study, she said.

EPA has hired experts in CH2M Hill’s Spokane office and will have a work plan by the fall. It will take two to four years to define the pollution problems, Grandinetti said.

Lake Roosevelt deserves a thorough Superfund study, including an analysis of Teck Cominco’s airborne pollutants from its tall stacks at Trail, a second pollution pathway that hasn’t been examined, said Lee, the Colville consultant.

“I have no doubt that the mercury in Lake Roosevelt is from Teck Cominco – from both pathways. Our analysis so far tells us this area is a cause for concern to tribal populations and anyone who eats more fish than folks in Iowa,” Lee said.

________________________________________________________________________

To view the actual article go to: http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2004/jun/20/bc-smelter-dumped-tons-of-mercury/

Teck deinies everything, until they are caught with their pants down.

They hide behind the Canadian flag.

This smelter regularly has spills and the fines imposed are much smaller than it would have cost to properly dispose of the toxins. Being tax deductible polluting is good for business.

LikeLike

Link to Environment Canada Pollutant Release Inventory Current to 2009:

Search on Trail Smelter NPRI ID: 3802

http://www.ec.gc.ca/pdb/websol/querysite/facility_substance_summary_e.cfm?opt_npri_id=0000003802&opt_report_year=2009

LikeLike